Programmes at Birkbeck's Institute of the Moving Image, 43 Gordon Square London WC1H 0PY

Raul Ruiz Resurrected

Following October’s Julian Henriques retrospective, BIMI will be offering a unique chance to see all three of the Raul Ruiz reconstructions that Poetastros in Santiago has produced in recent years in a special triple-bill on 8 November. All have been premiered to great acclaim in major festivals – The Wandering Soap Opera in Locarno; The Widower’s Tango at the Berlinale; and Socialist Realism at San Sebastian last year – but hitherto not seen in London. By arrangement with actress and producer Chamila Rodrigues, who has been the driving force behind these, they will finally reach London, where one of the earliest Ruiz retrospectives took place in 1981.

part of Ruiz’s ‘fictional documentary’.

He was also increasingly embraced by younger generations of Chilean cinephiles, valued as a link with the Chilean ‘new wave’ of the late 60s, as well as a prolific widely travelled figure. Rodriguez and her colleagues at Poetastros worked with Ruiz’s frequent collaborator and widow Valeria Sarmiento to ‘complete’ three unfinished works which display different aspects of Ruiz’s complex creative personality. The Widower’s Tango would have been his first film, in 1967, if the funding had been available to add sound. When the silent footage was discovered in a cinema basement, Poetastros managed to create a soundtrack. Socialist Realism was started during the hectic months of Allende’s Popular Unity government, dramatizing the conflicts between different supporters and opponents in typically sardonic Ruizian style. But it was unfinished when he and Sarmiento had to escape, and its material was scattered across different countries (a fragment was shown in Britain in 1981, which unfortunately disappeared). The Wandering Soap Opera was Ruiz’s surrealistic commentary on Chilean ‘reality’, which he saw as a battle between conflicting versions of the telenovelas beloved of Chilean television viewers.

There is still a vast amount of Ruiz’s enormous output to catch up on in Britain. But at least we can now see what his closest supporters have managed to salvage from this vast oeuvre. Time for the kind of retrospective that has been seen in Paris, New York and Vienna. Britain, and especially Scotland – where he held a teaching post at Aberdeen University – meant a lot to Ruiz. Surely time we repaid the compliment.

Ian Christie

F

Early Venetian Gothic

July 3, 2024 2 minutes

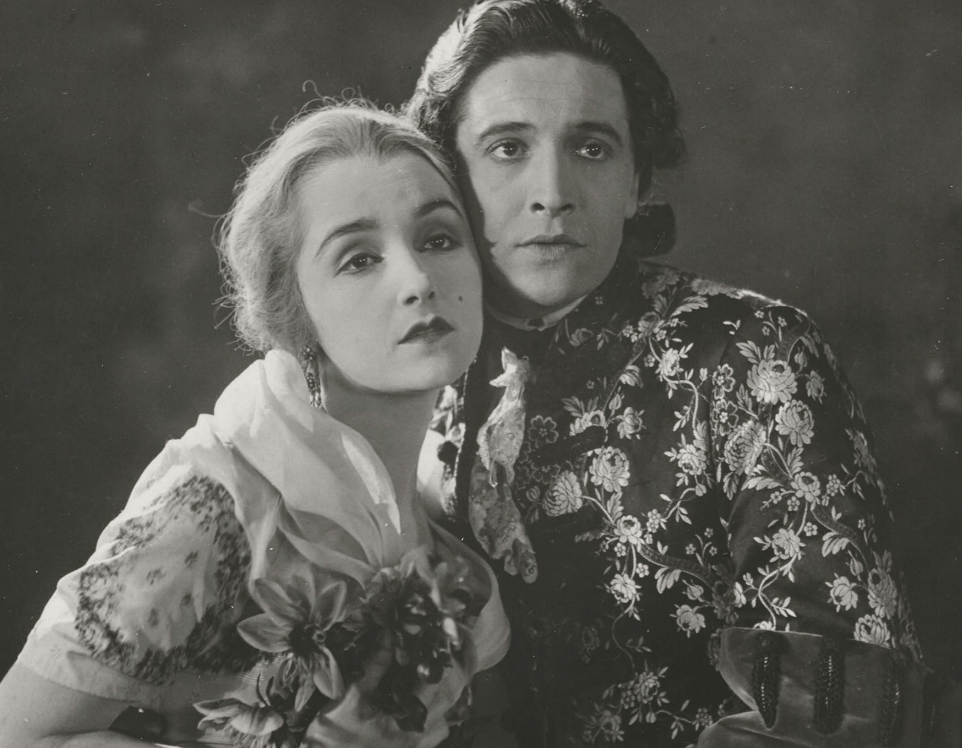

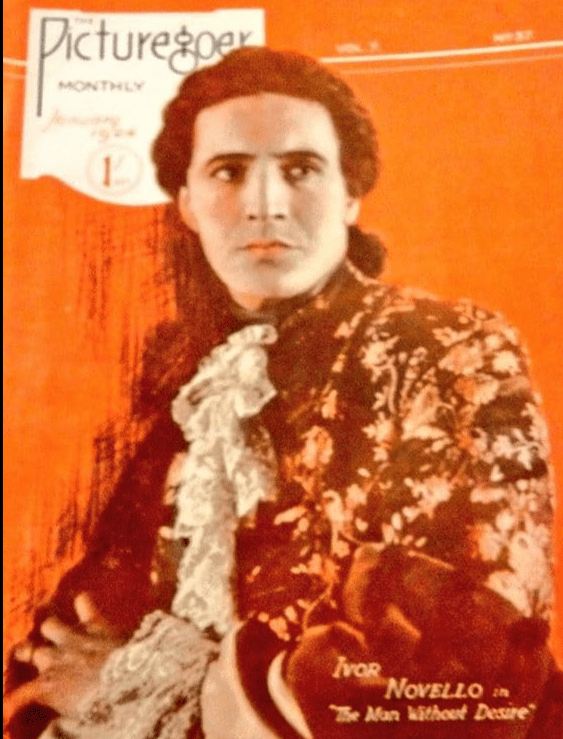

Nina Vanna and Ivor Novello in The Man Without Desire

BIMI’s end of term treat is a rare chance to see one of the outstanding early British silents, The Man Without Desire (1923), shown on 35mm with live piano accompaniment by Costas Fotopoulos. When it opened amid the excitement of Lang’s and Lubitsch’s great post-war films, Adrian Brunel’s first feature was hailed by leading critic C. A. Lejeune as ‘worth all the British Film Weeks put together’. Fifty years later, the normally sceptical Rachael Low praised it as ‘romantic and interestingly made’.

The film’s refined imagery, rare in British cinema of this period, owed much to being filmed on location in Venice and in a Berlin studio. Its cinematographer, Henry Harris, was fresh from working on Gance’s J’accuse, and would later shoot Asquith’s best silents. Above all, it launched Britain’s first authentic movie star, Ivor Novello, in a role ideally suited to his ‘otherworldly beauty and sexual ambiguity’ (Mark Duguid), partnered by Nina Vanna, who would later rejoin Novello in his Triumph of the Rat. Worth noting also that a contributor to the script, Monckton Hoffe, would go on to write Street Angel for Frank Borzage.

But maybe we should be locating Man Without Desire in Britain’s intermittent Gothic cinema: anticipating another time-travel romance, Terence Young’s Corridor of Mirrors (1948), or the haunted Venice of Nic Roeg’s Don’t Look Now. Sadly, Brunel would never again enjoy the same freedom to follow his instincts and create something ‘rich and strange’.

This screening will be introduced by BFI Archive curator Jo Botting, who recently published Adrian Brunel an British Cinema of the 1920s, subtitled ‘The Artist versus the Moneybags’ (EUP, 2023) And it will include an even rarer screening of Brunel’s satirical take on British filmmaking in the 20s, So This is Jollygood (1925).

Ukrainian Modernists on Soviet Screens

Friday 31 May * 6.30pm * Birkbeck Cinema

It’s a pity the Royal Academy’s otherwise timely show ‘Modernism in Ukraine’ makes no reference to the explosion of Ukrainian talent in early Soviet film. However, a programme at Birkbeck’s BIMI on Friday 31 May aims to remedy some of this omission. One crucial figure in this was Alexandra Exter, hailed by James Meek in the current Royal Academy magazine, as a ‘blazing talent’ who linked Paris, Moscow and Kyiv. One of the first to bring news of Cubism to Kyiv, she moved to Moscow to design avant-garde theatre settings and teach at the Vkhutemas modernist art school. This led to her designing the ‘Martian’ settings and costumes for Aelita (1924), Soviet cinema’s pioneering and widely influential sci-fi film.

One of Exter’s Kyiv pupils, Grigori Kozintsev, would join forces with Leonid Trauberg, originally from Odesa, in 1921 to launch an irreverent Futurist troupe, the Factory of the Eccentric Actor in Petrograd. After the FEKS’ outrageous film debut with The Adventures of Oktyabrina (poster above), they were chosen by the leading scholar Yuri Tynyanov to direct a radical version of The Overcoat, fusing this classic story with another, Nevsky Prospect, by Ukraine’s greatest writer Nikolai Gogol.

Understanding the tangled history of Ukraine’s pioneering artists during the 1920s isn’t easy, after they have routinely been conscripted into a ‘Soviet avant-garde’. But ahead of the Royal Academy exhibition that opens on 29 June, this programme demonstrates how crucial Ukrainian talent was to Soviet cinema’s legendary first decade.

With live piano accompaniment by Costas Fotopoulos for Chess Fever, The Overcoat and an extract from Aelita.

On sale: Eccentrism Turns 100 – all about FEKS with their original manifesto